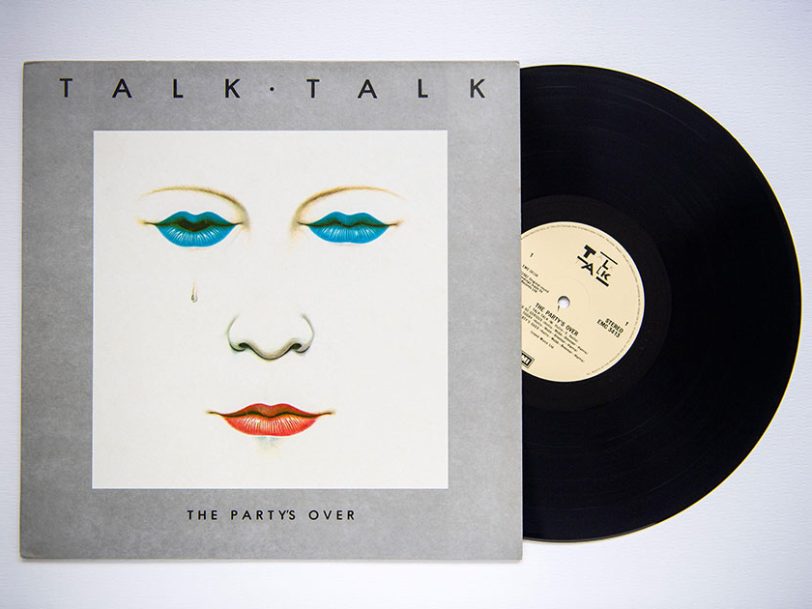

Most of the discussion surrounding Talk Talk’s debut album focuses these days on what it’s not: it’s not the art-pop turnaround of The Colour Of Spring or Spirit Of Eden – rightly revered records that, for some, have effectively deified the group’s late frontman, Mark Hollis – and it’s not the blockbuster synth-pop smash the band’s record label hoped it would be. But these observations overlook what the album is. Issued in the summer of 1982, The Party’s Over offered a clear indicator that, despite its contemporary production – and surface-level reaction from some quarters of the press – Talk Talk were never going to be of a piece with the New Romantic bands they were initially lumped in with. As NME noted at the time, their early music may have been catchy, but there was a “darker side; a gothic, almost celestial majesty” to the songs that made up The Party’s Over. Indeed, scratch beneath the surface and you’ll hear a confident group already shrugging off the restrictions of pop convention.

Listen to ‘The Party’s Over’ here.

“People who say that obviously haven’t listened to us properly”

Not that there wasn’t a precedent for the comparisons. Talk Talk had received crucial early exposure supporting Duran Duran during a UK tour at the end of 1981 and, aside from a penchant for repetitive naming, the two groups shared a producer, Colin Thurston, who had already helmed Duran Duran’s self-titled debut album and was working across their gargantuan follow-up, Rio, while also manning the boards for The Party’s Over.

Explaining the band name, Mark Hollis told Sounds that he liked the fact the group were named after one of their own songs: it was “really instant in terms of memorising it. Plus it didn’t in any way categorise us.” As to the musical comparisons with Duran Duran, an exasperated Hollis told Smash Hits that Talk Talk had been “compared to 11 different bands!” – a diverse bunch including Echo And The Bunnymen, Styx, U2 and Roxy Music – and that, “People who say that obviously haven’t listened to us properly.”