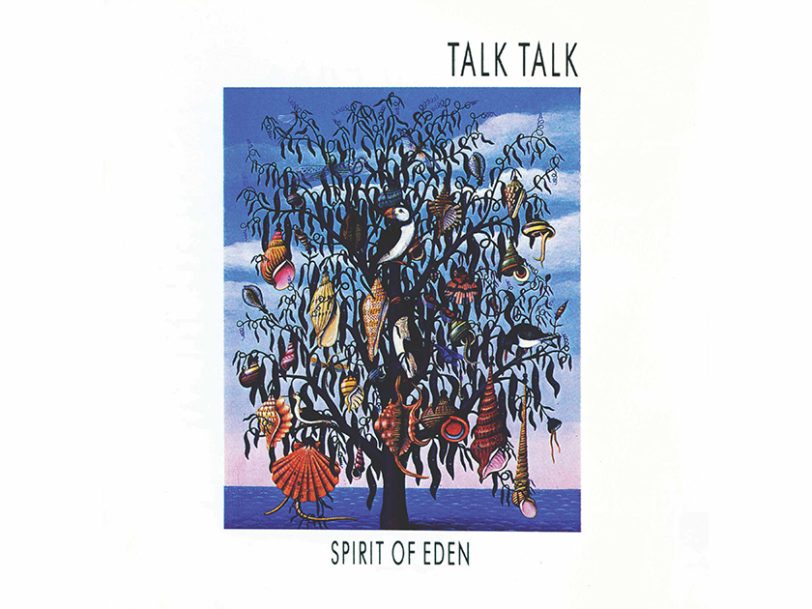

It’s fair to say Talk Talk’s fourth album, Spirit Of Eden, was one of the most intensely anticipated releases of 1988. Its predecessor, the sublime, two-million-selling The Colour Of Spring, had established the band as mainstream contenders who seemingly prioritised both artistic growth and commercial success, so the group’s record label, EMI, believed the only way was up from thereon in. Accordingly, Talk Talk were allowed full artistic control over their next record, as all around them were confident that the Mark Hollis-fronted outfit would again deliver.

Listen to ‘Spirit Of Eden’ here.

The backstory: “They didn’t know how to sell it”

Famously, EMI were aghast when Spirit Of Eden finally landed, following protracted studio sessions which lasted from May 1987 to March 1988. In public, both band and label put on a united front – in a contemporary interview with Q magazine, EMI’s then general manager, Tony Wadsworth, suggested the record was “like a cross between classical music and jazz with a modern perspective… I think it’ll be well received” – but behind the scenes, Spirit Of Eden’s contents induced something close to panic.

“There was real nervousness and misunderstanding about that record,” EMI’s Director Of Repertoire Nigel Reeve told The Guardian retrospectively in 2012. “Nobody got it. There wasn’t a hit single and they didn’t know how to sell it. It caused problems.”

With hindsight, Talk Talk hadn’t intended to create such apoplexy. The situation had only transpired because their single-minded frontman, Mark Hollis, was determined Spirit Of Eden should reflect his band’s continual evolution. Indeed, the interviews he undertook to promote the record bullishly reinforced that standpoint.

- Best Talk Talk Songs: 10 Sublime Tracks That Still Speak Wonders

- ‘The Party’s Over’: Why Talk Talk’s Debut Album Needs Celebrating

- ‘It’s My Life’: How Talk Talk Declared Independence From Synth-Pop

“It’s certainly a reaction to the music that’s around at the moment, ‘cos most of that is shit,” Hollis told Q in October 1988. “It’s only radical in the modern context. It’s not radical compared to what was happening 20 years ago. If we’d have delivered this album to the record company 20 years ago, they wouldn’t have batted an eyelid.”

In retrospect, Hollis had long been dropping hints that Talk Talk were about to embrace a more experimental approach. He had enthusiastically praised some of music history’s best jazz musicians, Miles Davis among them, along with genre-fusing Hungarian composer Béla Bartók in interviews dating back to the group’s The Colour Of Spring era, and these pioneering, free-thinking artists inspired Hollis and his team to encompass a much broader palette of sounds, ensuring Spirit Of Eden could push way beyond the traditional confines of pop.