Rowdy, rebellious and volatile, Irish band The Pogues somehow succeeded in spite of themselves. Initially naming themselves the deliberately provocative Pogue Mahone (Irish Gaelic for “kiss my arse”), the group revelled in their outsiders’ credo, yet their unique blend of punk-inflected Irish folk music connected with the mainstream and resulted in one of the most potent bodies of work known in any genre of music.

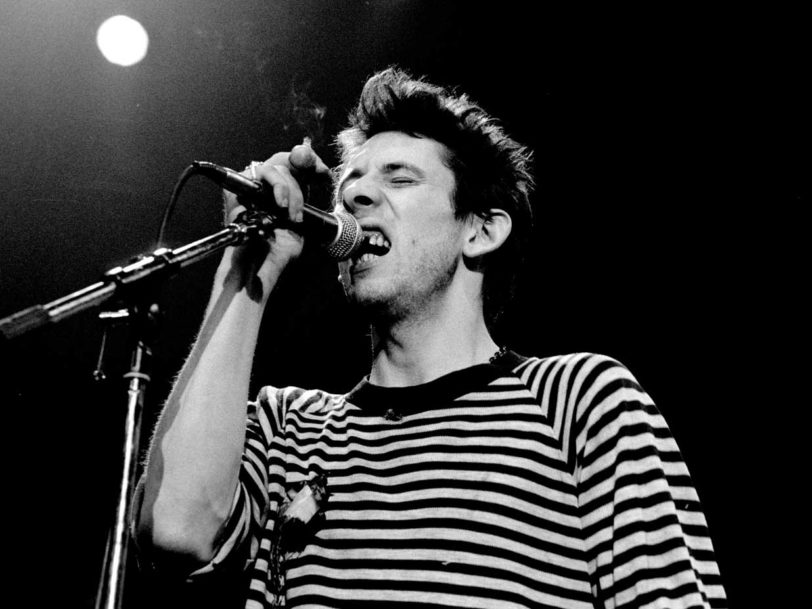

The Irish rover: Shane MacGowan’s early years

The “punk” part of The Pogues’ equation shaped their initial stance. Future Pogues frontman Shane MacGowan latched onto first-wave punk outfits such as The Clash and The Damned during their early days and – as Shane O’Hooligan – he formed his own punk/new wave outfit, The Nipple Erectors. Building a local following, the band played London punk haunt The Roxy and, after rebranding themselves as The Nips, released several promising singles, including Gabrielle and the Paul Weller-produced Happy Song.

MacGowan, however, had a markedly different background from most of his punk-era peers. Born to Irish parents in the English county of Kent, on Christmas Day 1957, he spent much of his early childhood in County Tipperary, Ireland. After winning a literature scholarship, he attended London’s Westminster School, where he was frequently bullied due to his looks and accent. Seeking refuge, the teenage MacGowan took to wandering London’s streets and found himself drawn to the capital’s less salubrious sights, among them the peep shows and strips joints of Soho. Much of what MacGowan witnessed in pre-gentrified London may not have been pleasant, but he later drew upon those experiences to illuminate some of his most singular songs.