There aren’t many groups who can truly claim to have radically shifted the parameters of pop music, but if anyone deserves that accolade, it’s Kraftwerk. Way ahead of the curve with a boundary-defying run of albums, from 1974’s Autobahn to 1981’s Computer World, the German electro pioneers predicted the future with their innovative use of synthesisers and self-built electronic percussion pads. As David Bowie put it: “The preponderance of electronic instruments convinced me that this was an area that I had to investigate a little further.”

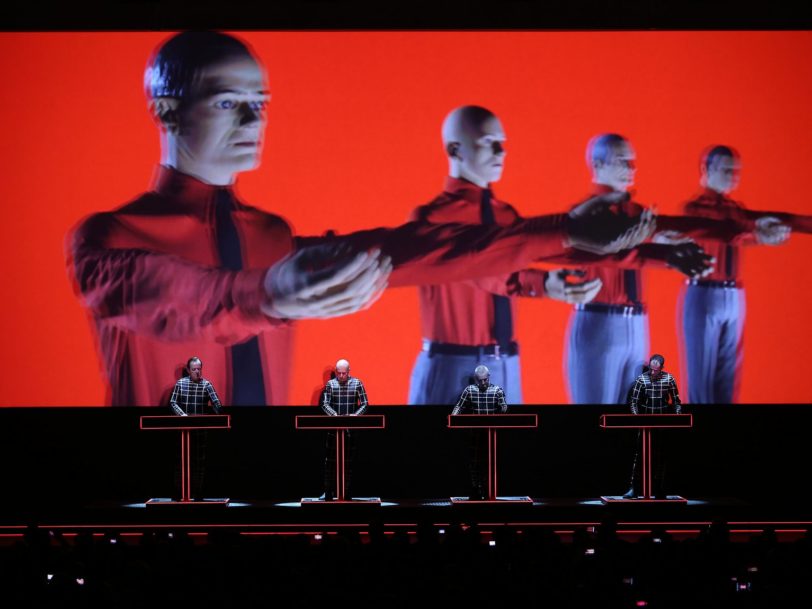

The groundbreaking shift in sound which Kraftwerk introduced not only inspired a legion of synth-pop disciples, it also set in motion the evolution of numerous other genres, among them hip-hop, techno and trance. By pre-empting the rise of 80s club culture and 90s rave music, the combined talents of Ralf Hütter, Florian Schneider, Karl Bartos and Wolfgang Flür birthed many sonic forebears, their radical prescience influencing pretty much every stripe of electronic dance music under the sun. Here’s how Kraftwerk forever changed the course of music as we know it…

Listen to the best of Kraftwerk here.

https://open.spotify.com/playlist/37i9dQZF1DX5NXgNrwh8I8?si=8eb24ee23fb5475f

“We had to redefine our musical culture”: Kraftwerk’s early years

Emerging from a disillusioned corner of a West Germany still reeling from the fallout of the Second World War, keyboardist Ralf Hütter and flautist Florian Schneider set out to revive a distinctly European sense of style unburdened by the political attitudes of the past. Eager to move his countrymen on to new sonic pastures, Hütter reflected, “We had to redefine our musical culture.” Uninterested in emulating the post-60s rock template imported from the US, Hütter and Schneider played with a band called Organisation on the 1970 album Tone Float, toying with meandering jazz influences much-loved by the “kosmische musik” scene. There were hints, however, of the duo’s fondness for electronic effects, as evidenced by Schneider’s use of studio manipulation to give his flute-playing an avant-garde twist.

When Organisation disbanded, Hütter and Schneider stuck together and built a recording studio west of Düsseldorf called Kling Klang. Working with drummers Andreas Hohmann and Klaus Dinger, they began recording under the guise of Kraftwerk, and released a self-titled debut album in late 1970. That record’s experimental fusion of lengthy instrumentals and cosmic soundscapes saw them searching for an identity, as did its two follow-ups, Kraftwerk 2 and Ralf And Florian. All three would, however, eventually come to be dismissed by the band as mere “archaeology”.

To this day, Kraftwerk’s early musical offerings remain difficult to find, but they offer plenty of alluring glimpses of the group’s undeniably original sound. Most notably, with the introduction of Wolfgang Flür – the man who helped Kraftwerk create their first electronic drum kit – the four-piece entirely phased human percussion out of their music.

“What we are doing is to make sound pictures of real environments”: ‘Autobahn’ and ‘Radio-Activity’

With a line-up of Ralf Hütter, Florian Schneider, Klaus Röder and Wolfgang Flür now in place, Kraftwerk’s big breakthrough came with their 1974 album, Autobahn, one of the first largely electronic pop records to meet with critical favour. Starkly engineered by Konrad “Conny” Plank and produced with austere beats, it was the culmination of Hütter and Schneider’s clinical, stripped-back use of synthesisers and the arty input of their friend and designer Emil Schult. Gone were the trappings of US rock’n’roll, in were minimalist, machine-like rhythms and synthetic melody lines. With lyrics romanticising Germany’s fabled high-speed road network, Kraftwerk had, for the first time, successfully distilled their electronic leanings to their essence while unashamedly displaying a Teutonic aesthetic inspired by modernist architecture.