In the early 2000s, Starsailor appeared to be that rare kind of band: seemingly arriving fully formed, they ignited a bidding war between major record labels before even releasing a single. By the time their debut album, Love Is Here, emerged, in the autumn of 2001, the group had come to exemplify everything NME had in mind when the paper coined the phrase “New Acoustic Movement”, a catch-all term for a growing breed of introspective bands – Travis, Doves and Coldplay among them – who were spearheading British rock music’s turn away from the boisterous braggadocio of Britpop in favour of heart-on-sleeve lyrics, tightly crafted melodies and, above all, a commitment to the purest fundamentals of songcraft.

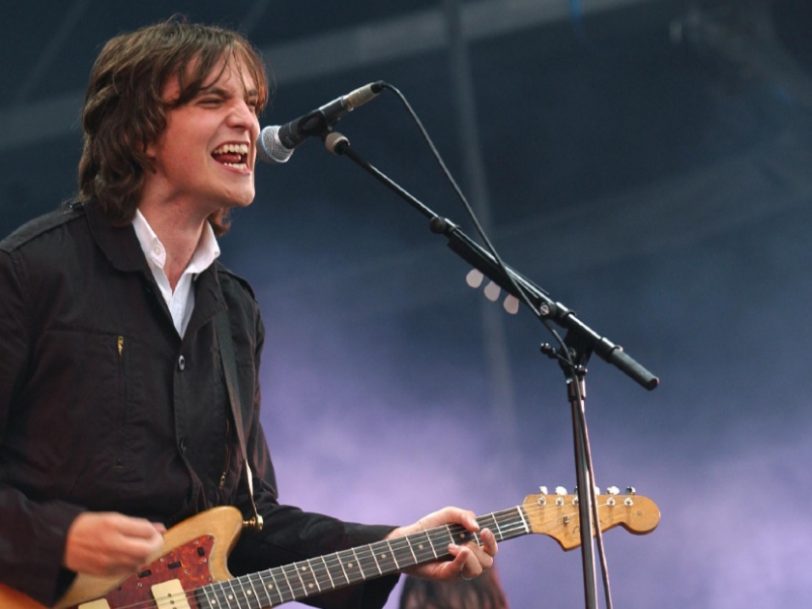

“We felt a kind of kinship that there was something happening and building,” frontman James Walsh tells Dig! of the scene in which Starsailor came to prominence. “It felt like a really exciting time.”

“It basically all comes down to having good songs,” bassist James Stelfox adds. “That’s what we all shared.”

Listen to ‘Love Is Here’ here.

“Stripping it back to basics gave us discipline”

“As soon as me and James met each other, we had this ambition to write songs,” Stelfox recalls of Starsailor’s formative years. The pair met just a couple of months after Walsh’s 16th birthday and immediately set out to realise their aspiration. As Walsh recalls, their early material sounded like the sum of their influences.

“I was still absorbing music, so listening to a lot of Oasis, Bluetones, Shed Seven, Charlatans – a lot of our early songs had that sound to them,” the singer says. “Gradually, Stel introduced me to Nick Drake. I started getting into Jeff Buckley and stealing my dad’s Neil Young records. The more influences we absorbed as we carried on developing the writing, the more original the sound became.”