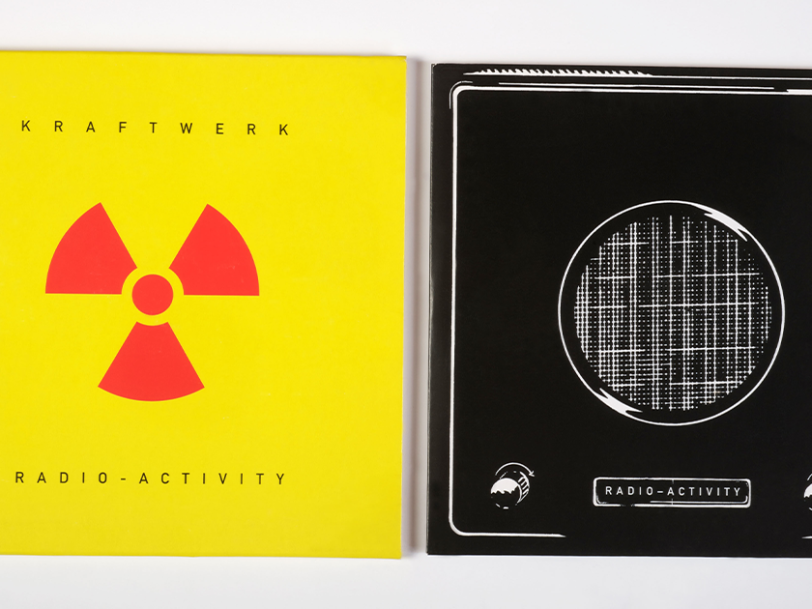

Following the runaway success of Autobahn – the groundbreaking 1974 album that brought Germany’s iconic motorway network to life – electro-pop pioneers Kraftwerk embarked on a tour of the US. While on the road, the four-piece of Ralf Hütter, Florian Schneider, Wolfgang Flür and Karl Bartos began to mull over their next musical adventure, eventually finding inspiration in a music magazine. “The original idea for the concept came from the Billboard charts where there is a column ‘Radioactivity’,” Bartos later revealed of the idea that sparked the group’s fifth album, the punningly titled Radio-Activity.

With their imaginations fired up by the limitless possibilities of exploring the concept of radioactivity – from radio waves that transmitted the sounds of popular music, to its more dangerous cousin in the form of nuclear energy – Kraftwerk returned home in early 1975 and began recording their most ambitious project yet in their Kling Klang studio in Düsseldorf. Unlike Autobahn, Radio-Activity would be the band’s first completely electronic record – and, better yet, it was a full concept album. Just like splitting the atom, Kraftwerk were on the brink of a historic new discovery.

“It was not a matter of our saying good or bad. We are not into morality, but realism”

Released in October 1975, Radio-Activity saw Kraftwerk push their electro-pop innovations further than ever before, introducing a unique synthetic choir-based effect to their sound thanks to a newly purchased Vako Orchestron keyboard. The eerie sounds of a Geiger counter intermingle with the static of a transistor radio before listeners are tuned into the gentle arpeggiated synth notes of the album’s title track.

Radioactivity, a six-minute meditation on the ubiquity of the universe’s most insidious source of energy, is an absorbing synth-pop tone poem that sees Ralf Hütter recite lyrics with typically muted emotion (“Radioactivity/Is in the air for you and me/Discovered by Madame Curie”). Released as a single in May 1976, it failed to chart anywhere except Belgium, but nonetheless went on to sell a whopping 500,000 copies in France. As a result, it is rightfully regarded today as one of the best Kraftwerk songs and hailed by Andy McCluskey as one of the key inspirations behind British synth-pop outfit Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark.

At the time of Radio-Activity’s release, music critics did not quite know how to interpret Kraftwerk’s ambivalent stance towards nuclear energy. This possibly wasn’t helped by the way the band chose to promote the album. “They [our record company] sent us into a real Atomkraftwerk [nuclear power plant] for silly promo pics,” Karl Bartos later reflected. “During the shooting I seem to remember that we suddenly had strange feelings.” With photos showing the group dressed in white protective suits and anti-radiation bags on their shoes, it wasn’t obvious whether Kraftwerk were endorsing nuclear power or were, in fact, just co-opting the idea as a canny artistic statement.

In a 1977 interview, Ralf Hütter attempted to set the record straight. “It was not a matter of our saying good or bad,” Hütter said. “We are not into morality, but realism.” Nevertheless, Kraftwerk would rework the song in 1991 to clarify their position. Their live shows began to include overt lyrical references to notable meltdowns such as the Three Mile Island accident and the Chernobyl disaster, imploring the powers that be to “stop radioactivity”. Today, it’s clear where they stand on the nuclear issue.

“Suddenly, there was a theme in the air: the activity of radio stations”

The idea of energy being a part of everyday life wasn’t just limited to radioactivity: the album’s next track, the slow and ethereal Radioland, taps into radio waves. “Suddenly, there was a theme in the air: the activity of radio stations,” Wolfgang Flür said. Having spent their youths toying with short-wave radio bands in their childhood bedrooms, the idea of making wholly electronic music to convey the idea of invisible electrical currents transmitting sounds into listeners’ ears was a master-stroke. “Radio has always fascinated us deeply,” Hütter would go on to say.

Using their synth-based ingenuity to celebrate the wonder of radio communication, Airwaves coasts along to a woozy Moog hook as Hütter speaks in his native tongue of how music brings people together (translation: “When airwaves swing/Distant voices sing”). In the spirit of the great modernists of the past, Kraftwerk see radio as a positive technological development worth praising, responsible for beaming far-flung sounds into our collective antennae.

Radio is not all about music, however, as, following a short intermission, the muffled voices of German news readers can be heard on the track News, discussing the future of nuclear energy. In our electronic age, the world hums with the sound of disembodied voices, but none are as sinister as those heard on The Voice Of Energy, an experimental track on which Kraftwerk use a bubbling vocoder effect for lyrics which envision electricity as an omnipotent god lurking in the shadows (translation: “I am your servant and lord at the same time/Therefore guard me well/Me, the Genius of Energy”). Ambivalent as ever, the group detects danger as well as promise in the wireless, much like in the subatomic threats of radioactivity itself.

“We saw ourselves, Kraftwerk, in the Kling Klang studio, to be a kind of radio station of our own”

The themes of radio communication are further explored on the spooky and ominous synth-pop groove of Antenna (“I’m the antenna, catching vibration/You’re the transmitter/Give information!”), while the shrill tocsin of Radio Stars puts a cosmic spin on proceedings, offering a reminder of how the waves of energy produced by quasars and pulsars occur naturally in deep space. Elsewhere, Kraftwerk don kid gloves to handle more volatile materials on Uranium. Set to a haunting Vako Orchestron choir backing and vocoderised spoken-word vocals, a gravelly German voice speaks of radioactive decay, soaking the listener in a foreboding synth-saturated air of resigned acceptance.

Plugged into a frequency of their very own making, the songs on the Radio-Activity album feel like an experimental radio broadcast as chilling and as alarming as Orson Welles’ 1938 War Of The Worlds faux-news bulletin. “We saw ourselves, Kraftwerk, in the Kling Klang studio as a radio station,” Ralf Hütter admitted. As the album drifts seamlessly into the spiralling synth instrumental of Transistor, the group place listeners back in radioland once again.

Radio-Activity’s final track, Ohm Sweet Ohm, is altogether more playful, with a robotic mantra ironically juxtaposing hippie obsessions with Transcendental Meditation with a scientific measure of electrical resistance outlined by Ohm’s Law. With a charming synth-pop melody, it’s a classical-inspired song that perfectly rounds off the album’s conceptual themes. A sweet-sounding ode to energy, both generative and decaying, Ohm Sweet Ohm brings zen-like closure to Radio-Activity’s more fretful and anxiety-ridden moments.

“We always considered ourselves the second generation of electronic explorers”

Upon its release, Radio-Activity peaked at No.22 in the German charts but proved to be more popular in France, where it went to No.1. While it is acknowledged today as a seminal work of art, Radio-Activity didn’t manage to emulate the success of Autobahn, but it was nonetheless a significant musical evolution for Kraftwerk. With great moments of melodic beauty, the album encouraged the band to abandon traditional instrumentation entirely, as well as to explore some darker, more disquieting soundscapes.

Taken as a whole, Radio-Activity is, indeed, a wilfully experimental concept album combining pop melodies with a more minimalist and understated approach while still tackling avant-garde sound-collage techniques. “We always considered ourselves the second generation of electronic explorers, after Stockhausen,” Ralf Hütter said in 1991. As one of the earliest pioneers of electronic music, Karlheinz Stockhausen was undoubtedly an influence on Kraftwerk’s music, from their love of musique concrète to their new-found use of Vako Orchestron-led choral soundscapes.

Not only would it be fair to consider Radio-Activity one of the best Kraftwerk albums, but it was also their bravest and most artful work up until that point, taking considerable risks musically while also wrestling with more controversial themes that could have threatened to alienate the group’s fan base. By venturing into more intellectual concepts, however, Radio-Activity proved to be a sign of things to come for Kraftwerk as they transferred their energy to their next project, the landmark 1977 album Trans-Europe Express.

Find out more about Kraftwerk’s pioneering electro legacy.

More Like This

Peter Tosh: The Bush Doctor’s Life, Music, Influence And Legacy

After finding fame with The Wailers, Peter Tosh struck out on his own. His uncompromising voice continues to resonate today.

Gary Kemp At 65: From Spandau Ballet Icon To ‘Rockonteurs’ Host

The creative force behind New Romantic icons Spandau Ballet, Gary Kemp endures today as one of the elder statesmen of pop music.

Be the first to know

Stay up-to-date with the latest music news, new releases, special offers and other discounts!