“There explains the difference between mere mortals and Prince”

In the early 80s, Prince’s music had taken on a new political hue, with the Dirty Mind and Controversy albums featuring songs such as Partyup and Ronnie, Talk To Russia which spoke more directly to world events than any other tracks he had released up to that point. In recording the song 1999, Prince entered a true purple patch, weaving Cold War paranoia, end-of-days prophesies and his own sexual revolution into a unified whole that stands as a landmark moment in his career.

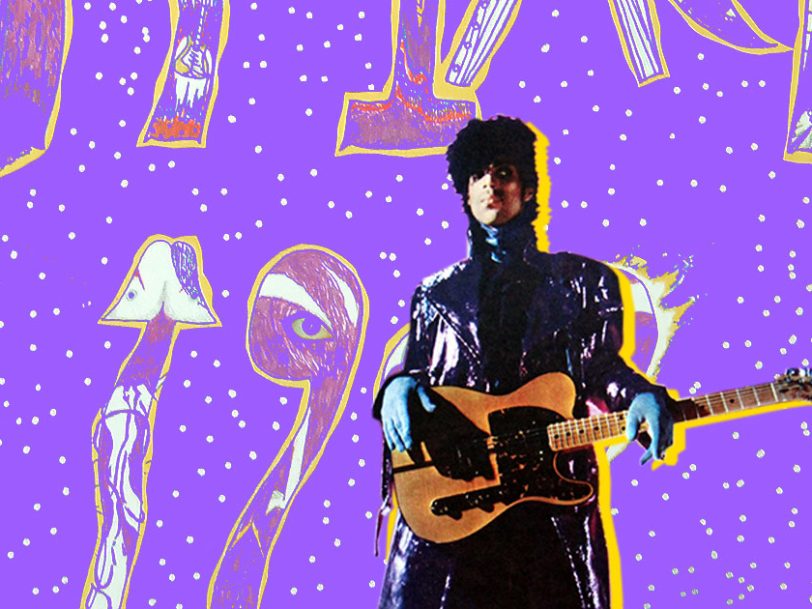

According to Prince’s then drummer, Bobby “Z” Rivkin, the inspiration for the song came from an HBO documentary Prince and his band watched together one night on tour. Titled The Man Who Saw Tomorrow, it was “about Nostradamus and the prediction of the end of the world, 1999, and we’re all blown away by this thing”, Rivkin told Minneapolis radio station The Current in 2018. “You could feel it in the hotel room. Just glued to the TV.” Recalling how the documentary became a talking point the next day, Rivkin noted that Prince’s reaction was to write a song about it. “We’re all going ‘wow’ and then he just embodied the whole thing with 1999… So there explains the difference between mere mortals and Prince.”

Opening with Prince intoning in a pitch-shifted, God-like voice, “Don’t worry, I won’t hurt you. I only want you to have some fun,” 1999 offers six minutes of hedonistic revelry in the face of Armageddon. A second manipulated vocal – the high-pitched “Mommy, why does everybody have a bomb?” – brings the song to its unsettling close; in between, Prince deploys a taut mix of funk guitar, synth-pop hooks and precision-tooled drum-machine patterns that not only reinforce his declaration, “So if I’m gonna die, I’m gonna listen to my body tonight,” but also mark the defining elements of the “Minneapolis sound” – a funk-pop concoction many of the best 80s songs would try to emulate as the remainder of the decade unfolded.