The 70s began ominously for Grateful Dead. The band had been busted by plain-clothes policemen following a show in New Orleans on 31 January 1970. They were in debt to their label, Warner Bros, after sales of their first three studio albums had struggled to recoup the costs of recording them. In February, they discovered that their then manager, Lenny Hart (father of drummer Mickey), had been embezzling funds from the band; when taken to task, Hart fled to Mexico, leaving the group in dire financial straits. It was a set of circumstances that would leave any band reeling but, that same month, the group recorded Workingman’s Dead, a landmark album that saw Grateful Dead adopt a new sound and sensibility, changing their fortunes forever.

Listen to ‘Workingman’s Dead’ here.

In many ways, the Dead were shaped by the challenges they faced. Their financial situation forced them to rehearse and record Workingman’s Dead in a matter of weeks at Pacific High Recording, a modest San Francisco studio located just around the corner from the Fillmore West. Running up a huge studio bill while experimenting with the possibilities of studio recording was not on the agenda this time around. For these sessions to work, the material had to be written and rehearsed beforehand – a convention that the freewheeling Dead had previously only flirted with.

“It was the first record that we made together as a group”

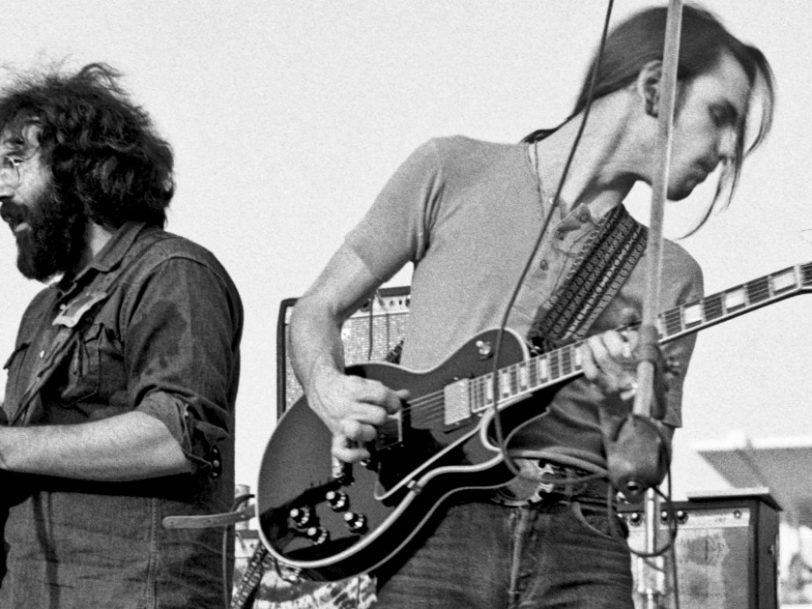

In a Rolling Stone interview around the release of Workingman’s Dead, the group’s lynchpin, Jerry Garcia, reflected on the effect that misfortune had had on the group’s mentality. “Being able to do that was extremely positive in the midst of all this adverse stuff that was happening,” he said. “It was definitely an upper… it was the first record that we made together as a group, all of us. Everybody contributed beautifully, and it came off really nicely.”

With their loyal engineers Bob Matthews and Betty Cantor on production duties, the band rehearsed the songs at Pacific High for a week. Matthews then took the best recordings of each and arranged them into a running order informed by the themes that emerged – work, journeys, the natural world, mortality. Impressed, the band went with it. As Matthews told Buzz Poole, author of the 33⅓ book on Workingman’s Dead, “When we went into the studio, the concept was in place. The recording was a delight.” Songs agreed, the Dead honed them with another week’s rehearsal, and Workingman’s Dead was ready to record.