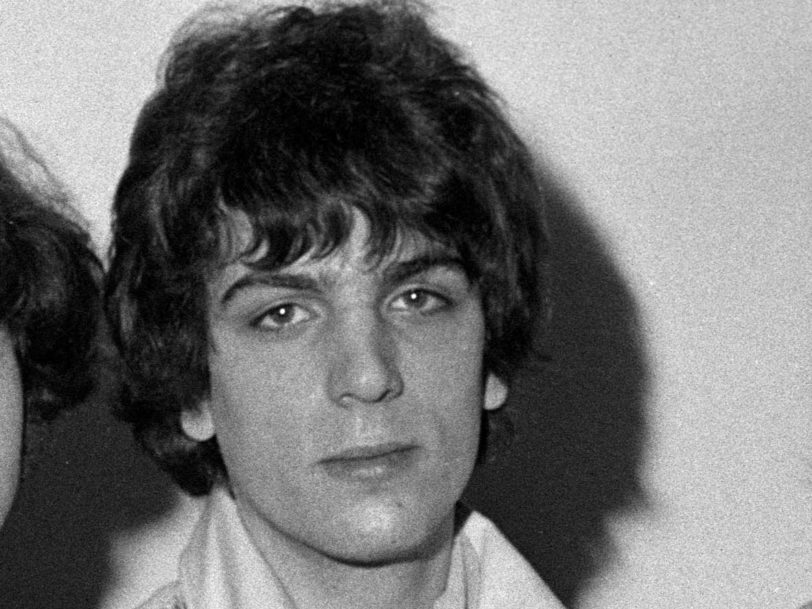

There have been few rock stars as enigmatic or as captivating as Syd Barrett. With his dark curly hair and his far-off gaze, the Pink Floyd co-founder dressed like a windswept enchanter from the pages of a long-lost fairy tale and wielded his mirrored Fender Esquire like a wand. What set Syd apart from others was that, beneath his paisley shirt, there beat the heart and soul of a poet, beholden to many age-old bohemian ideals – a love of art, beauty and wonder.

As the co-founder of Pink Floyd, Syd Barrett burst onto the 60s music scene, proving himself a highly original songwriter not just playfully adding numerous literary references to Pink Floyd’s songs, but also revolutionising how rock’n’roll could take you on a trip you’ll never forget. In doing so, Syd became an icon who would be similarly unforgettable, long after he’d exited the stage.

The story of Syd Barrett’s life – from his musically-inspired highs to his drug-related lows – has seen him mythologised as one of rock’s most famous acid casualties, alongside the likes of Peter Green and Brian Wilson, which tends to overshadow his achievements as a musician. This is unfortunate, as listening to Syd’s music reveals a truly unorthodox soul who embodied the transcendental power of psychedelic rock more than anybody else.

This “madcap” genius deserves to have the last laugh…

Hanging In My Infant Air: Birth And Childhood

Born in Cambridge, on 6 January 1946, Roger “Syd” Barrett enjoyed most of his childhood years with a love of drawing and poetry, inspired by the English countryside near the Gog Magog Hills – a land full of scarecrows and ancient oak trees. As a child, Barrett would read Cautionary Tales by Hilaire Belloc and Wind In The Willows by Kenneth Grahame, drawn to a fantasy world of magic and anthropomorphic creatures.

Around this time, the young Roger was nicknamed “Syd”, due to a flat cap he wore during his time in the Boy Scouts, as many of his friends made humorous digs at his working-class attire. It wasn’t until Syd got his first guitar at 14 – a Hofner acoustic – that he started to add music to his creative interests. Tragically, his father died of cancer the following year, affecting Syd hugely and hurling him deeper into his own artistic pursuits.

In response to his father’s death, Syd channelled most of his energies into painting, though as a teenager in 1962 he played rhythm guitar in a band called Geoff Mott And Mottoes, performing covers of Bo Diddley and The Shadows songs. Like many 60s rockers, Barrett’s quest really only began after he left home and enrolled at art school, in 1964. Heading to London’s Camberwell College, Syd found himself inspired by artists like Mark Rothko and Robert Rauschenberg, mixing abstract expressionism with his own musical ambitions.

Action Brings Good Fortune: The Pink Floyd Sound

Despite his love of art, Syd continued to find himself drawn to music. He joined a band with his childhood friend Roger Waters, who at the time also happened to be studying in London at Regent Street Polytechnic, along with fellow-bandmates Richard Wright, Nick Mason and Bob Klose (who would eventually leave the group in 1965). Initially called The Tea Set, it was Syd who was credited with coming up with the band’s name – The Pink Floyd Sound – by combining the names of blues singers Pink Anderson and Floyd Council.

Beyond naming them, however, Syd’s musical influence was keenly felt from the offset. As their frontman, Syd’s pioneering use of the Binson Echorec delayed-echo device would eventually find favour in the nascent underground scene in Britain. By 1966, the group, now naming themselves Pink Floyd, began to play free-form jams inspired as much by jazz as they were by R&B and the blues, hosting elaborate light shows at London’s UFO Club and soundtracking them with groundbreaking and exploratory compositions such as Interstellar Overdrive.