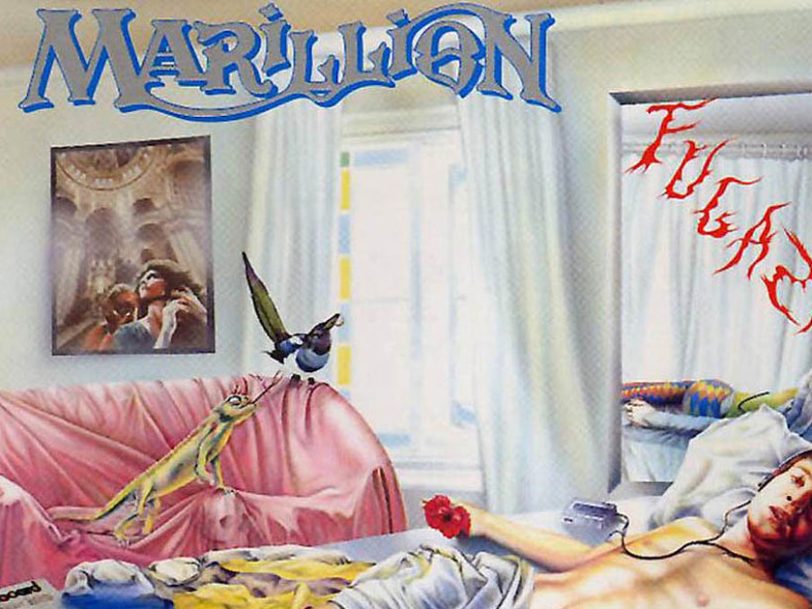

Surviving the conflicting strains of a rushed songwriting process and protracted recording sessions, Marillion’s sophomore effort, Fugazi, has long been considered by the band to be their “difficult second album”. In spite of this, the record’s timely fusion of mid-80s synth-pop with progressive rock, aided by frontman Fish’s alluring and multifaceted poetic whimsy, has steadily grown into a cult favourite among the band’s fans.

By the end of 1983, Marillion’s debut album, Script For A Jester’s Tear, had been an unmitigated success, selling more than 300,000 copies in the UK. With expectations quickly rising, frontman/lyricist Fish, guitarist Steve Rothery, keyboardist Mark Kelly and bassist Pete Trewavas soon had to contend with the departure of their original drummer, Mick Pointer, before facing down a litany of challenges that almost threatened to derail the group’s progress.

Here is the story of the tumultuous creative process from which Marillion’s Fugazi emerged, and why the album marks an important chapter in the neo-prog band’s early career…

Listen to ‘Fugazi’ here.

The backstory: “We were still trying to make a name for ourselves and bust out of the divisions”

Caught up in promoting their debut album, Marillion were already feeling the pressure to record a follow-up. Despite their numerous touring commitments, a new record was expected to be finished within a year, but with very little time to write songs and feeling tired from life on the road, that seemed a hard ask. To make matters worse, the sudden dismissal of drummer Mick Pointer meant that Marillion’s line-up was in a state of flux.

As the band headed off to Wales on a brief writing retreat, Andy Ward, the former drummer for prog-rock band Camel, temporarily joined the group and they began to throw together some early ideas. At this point, Fish had a notebook filled with unused lyrics, but Marillion hadn’t been working on new material for very long before they were sent back out on the road, this time for a US tour. It was during these shows that Ward left and handed over the drumsticks to John Marter, who played with Marillion when they supported Rush in New York City.