Have you ever been listening to a song for the first time, and sworn you’d heard it somewhere else before? Chances are, you probably have. Music is an art form in which musicians are continually inspired by each other’s work, adapting it in various ways. As some of the biggest copyright lawsuits in music history have shown, however, there is a fine line between inspiration and plagiarism. Here are ten landmark copyright lawsuits that have defined the course of popular music.

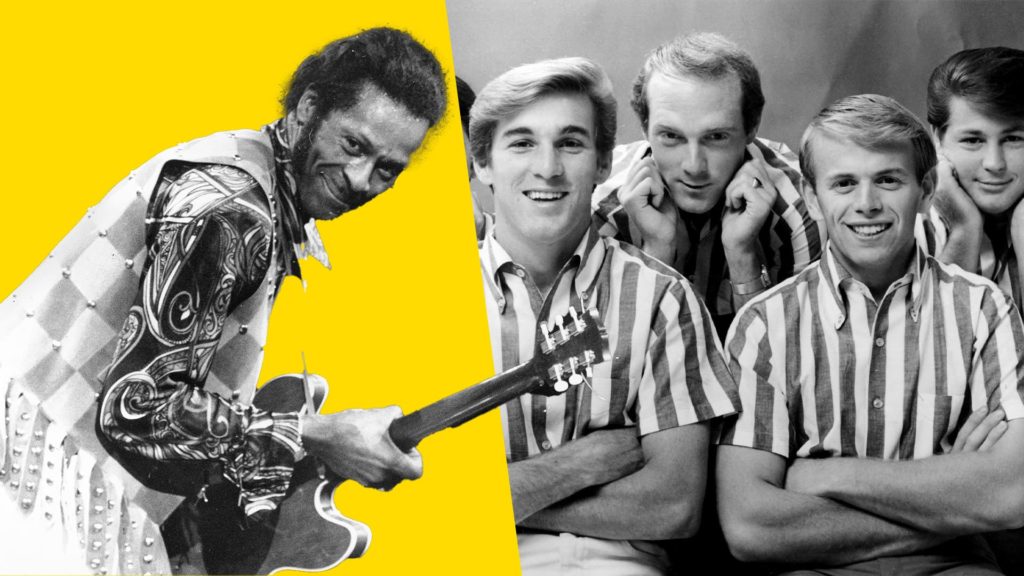

Chuck Berry vs The Beach Boys (1963)

The songs

Sweet Little Sixteen (1958) and Surfin’ USA (1963)

The background

In 1963, The Beach Boys released Surfin’ USA, an instant classic that captured the optimistic essence of the West Coast surf scene. The song was, however, a lift of Chuck Berry’s Sweet Little Sixteen, with new lyrics written by Beach Boys Brian Wilson and Mike Love.

The legal case

Berry’s song was about a teenage girl who dreams of dancing her way across the American bandstands, listing the various cities she would “rock” around; The Beach Boys simply tweaked this idea and listed the various US beaches surfers were flocking to. One of the more overt cases of white popular music appropriating the sounds of black America, Brian Wilson has said he didn’t mean any harm with Surfin’ USA, and that the song – The Beach Boys’ first Top 5 US hit – was recorded in tribute to one of their rock’n’roll idols.

The verdict

When approached about the theft, The Beach Boys’ then manager (and Brian Wilson’s father), Murray Wilson, immediately gave Berry the copyright to the song in order to avoid a lawsuit. Berry now receives credit alongside Wilson for the tune.

Chuck Berry vs John Lennon (1973)

The songs

You Can’t Catch Me (1956) and Come Together (1969)

The background

As one of the original rock’n’roll pioneers, Chuck Berry influenced everyone from Bob Dylan to The Rolling Stones. The Beatles made no secret of their love for him, covering Roll Over Beethoven on their second album, 1963’s With The Beatles, and returning to the Berry songbook again for Rock And Roll Music (on the following year’s Beatles For Sale album). By the end of the decade, however, they would find themselves on the end of one of their hero’s copyright lawsuits.

The legal case

While writing their 1969 song Come Together, John Lennon looked to Berry for inspiration, adapting a line from his 1956 single You Can’t Catch Me – “Here come a flat top/He was movin’ up with me” – for his own song’s opening lyric, “Here come old flat top/He come groovin’ up slowly”, and emphasising the same vowels as Berry when he sang it. Though, musically, Come Together was given a slower, funkier arrangement than You Can’t Catch Me, Berry’s publisher, Morris Levy, owner of Big Seven Music, started legal proceedings against Lennon, resulting in a serious of copyright lawsuits between both parties.

The verdict

Settling the initial dispute out of court, Lennon agreed as part of the deal to record three Big Seven Music songs on his next album. In the event, his 1975 album, Rock’n’Roll, only included two Big Seven Music tunes, a take on Lee Dorsey’s 1961 cut Ya Ya and a cover of the Chuck Berry song that started it all: You Can’t Catch Me. Once Levy noticed that Lennon – already in breach of their agreement – had given You Can’t Catch Me an arrangement that skirted closer to The Beatles’ Come Together than it did Berry’s original track, Levy again initiated legal proceedings, and the court awarded him $6,795.

The matter didn’t end there. While choosing songs to include on Rock’n’Roll, Lennon had sent Levy a tape of demo recordings, which Levy subsequently released through Big Seven Music as Roots: John Lennon Sings The Great Rock & Roll Hits. Inevitably, another round of copyright lawsuits flew as Lennon took Big Seven Music to court. Lennon, Capitol Records and EMI came away with $109,700 in lost royalties, while Lennon himself received a further $35,000 in compensation for damages.

The Chiffons vs George Harrison (1976)

The songs

He’s So Fine (1963) and My Sweet Lord (1971)

The background

In 1971, George Harrison released his hit solo single My Sweet Lord, which, with its catchy rhythm guitar and lyrics concerning spiritual enlightenment (with a unique blend of typically Christian imagery with Hare Krishna chants), remained at No.1 for four consecutive weeks.

Harrison later said My Sweet Lord had been inspired by the two-chord progression of “Hallelujahs” The Edward Hawkins Singers’ sang on their version of the 18th-century hymn Oh Happy Day, but with My Sweet Lord riding high in the charts and receiving constant radio play, many noticed its similarity to The Chiffons’ 1963 US No.1, He’s So Fine.

The legal case

Lyrically, He’s So Fine evokes a youthful longing for one particularly good-looking guy. The fact that its musical DNA later became part of Harrison’s spiritual quest for God shows how the fundamentals of a timeless pop hit can find their way into other artists’ work – whether consciously or unconsciously.

One of the main determinants of copyright lawsuits is whether the artist had access to the original song. In George Harrison’s case, there was no doubt he had heard He’s So Fine: not only a huge hit in its own right, The Beatles had covered many black girl-group songs in their early days. Seeing a clear case, Bright Tunes Music Corporation, who owned the rights to The Chiffons’ song, started legal proceedings.

While Harrison’s then manager, Allen Klein, initially offered to buy the entirety of Bright Tunes’ catalogue, Bright Tunes felt more money could be made from the ex-Beatle if they went to court. After a four-year stalemate, the case went to trial in 1976, with Bright Eyes basing their evidence on musical motifs in He’s So Fine that were repeated in My Sweet Lord, notably “Motif A”, with which they proved Harrison had based the opening line of his song on the opening line of The Chiffons’ hit. Though performed in different keys, the notes and melodies in both songs are nearly identical. Harrison claimed this was a subconscious lift rather than an overt act of plagiarism.

The verdict

The case’s presiding judge, Richard Owen, of the US District Court in Manhattan, agreed: “Did Harrison deliberately use the music of He’s So Fine?” he asked, concluding, “I do not believe he did so deliberately. Nevertheless, it is clear that My Sweet Lord is the very same song as He’s So Fine with different words, and Harrison had access to He’s So Fine.” Harrison paid $1,599,987 in damages, later writing the sardonic This Song about the experience: “This song ain’t black or white and as far as I know/Don’t infringe on anyone’s copyright.” So far, no copyright lawsuits have emerged over that one…