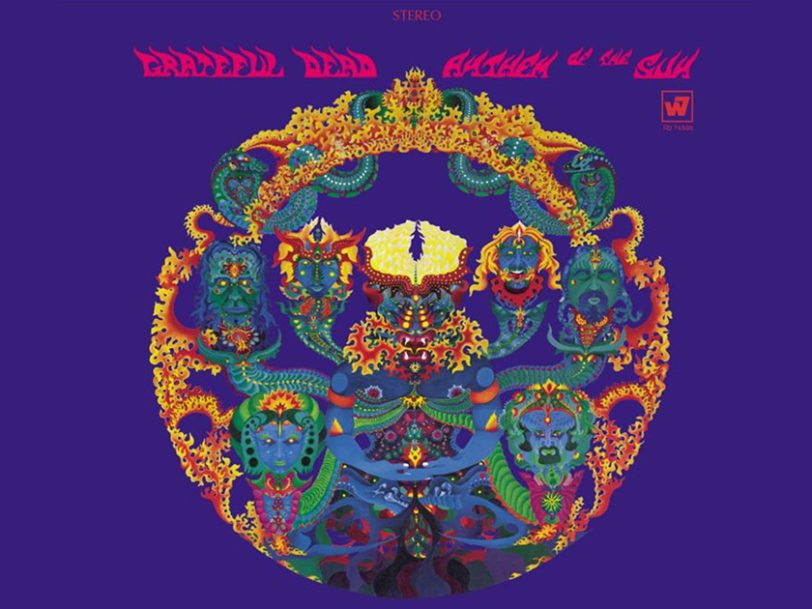

Released in the summer of 1968, Grateful Dead’s second album, Anthem Of The Sun, came at a pivotal time for the San Francisco jam band.

Recording sessions began at American Studios, in Los Angeles, in November 1967. A few months previously, percussionist Mickey Hart had joined the group – his interest in polyrhythms, jazz and African music would be integral to the Dead’s development. The album also featured the group’s first collaboration with Robert Hunter (on the song Alligator), the lyricist who would do so much to put the band’s worldview into words in the coming decades.

Listen to ‘Anthem Of The Sun’ here.

The backstory: “We weren’t making a record in the normal sense; we were making a collage”

The Dead were up against it. Their self-titled debut album had struggled to capture the free-flowing psychedelic abandon of their live shows and had been overshadowed by the release of Surrealistic Pillow, the second album by their San Francisco neighbours Jefferson Airplane. Meanwhile, there was a post-“Summer Of Love” backlash against the hippie movement, as drugs took hold of San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury scene and the area became a magnet for burnouts with little in common with the movement’s original ethos. On 2 October 1967, the Dead’s communal home, at 710 Ashbury Street, was raided by the police after an informant set them up, resulting in band members Bob Weir and Ron “Pigpen” McKernan being charged with marijuana possession.

Despite, or perhaps because of, the increased pressure, those initial recording sessions for Anthem Of The Sun didn’t go to plan. The band reunited with producer Dave Hassinger, who had overseen sessions for their debut album and been The Rolling Stones’ chief US studio engineer from late 1964 to August 1966, as well as having worked with Jefferson Airplane, Love and Electric Prunes, among many other countercultural figures. But though Hassinger seemed like a good fit, the Dead were a different proposition from any of his other clients.

The recording: “The most unreasonable project with which we have ever involved ourselves”

A group constantly straining against convention and pre-conceived notions of what musicians should do and how they should behave, the Dead were determined to lead the Anthem Of The Sun sessions in their own way. They were also still relatively new to studio recording and struggled to lay down definitive takes of their songs in such relatively unfamiliar conditions. Dissatisfied with the results in LA, the Dead relocated to New York City and attempted to keep things moving in Century Sound and Olmstead Sound studios.

Hassinger suggested they sing as a group to cover up imperfections, an idea rejected by the band. At one point, guitarist Bob Weir requested that they record “thick air”. Weir later said, in Oliver Trager’s 1997 book, The American Book Of The Dead, “I couldn’t describe it back then, because I didn’t know what I was talking about. I do know now: a little bit of white noise and a little bit of compression. I was thinking about something kind of like the buzzing that you hear in your ears in a hot, sticky summer day.” For Hassinger, it was all too much; the producer quit the sessions.