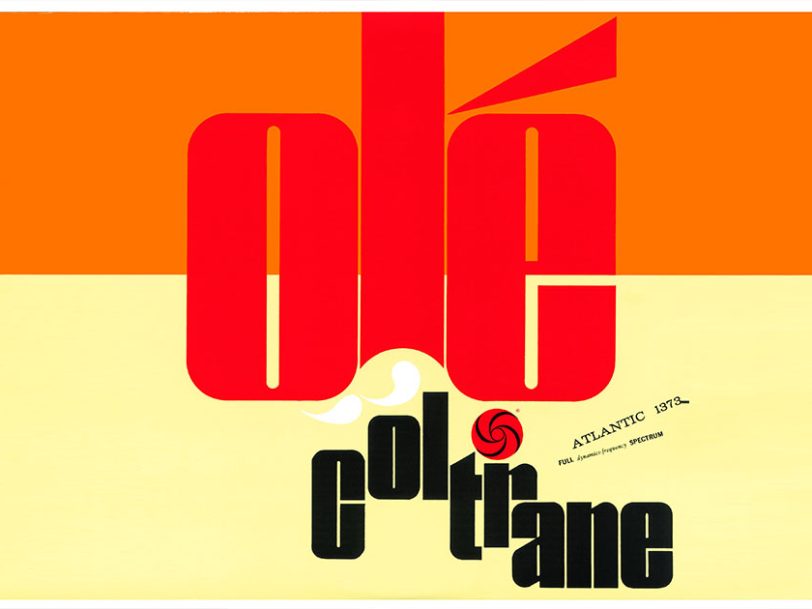

25 May 1961 is best remembered as the day that President John F Kennedy announced to the US Congress his government’s ambitious intention to put an American on the Moon before the decade’s end. But it also marked a significant event in jazz history: it was the day when John Coltrane arrived at New York City’s A&R Studios, knowing that he was about to undertake his final recording session for Atlantic Records, resulting Olé Coltrane, a pivotal release in Coltrane’s canon.

A shining beacon of instrumental virtuosity

The Philadelphia-based saxophonist had been with Atlantic for just over two years and, in that short time, had made some momentous recordings as well as taken giant strides forward in his own musical and personal development. But it was time for a change and, feeling that his future lay elsewhere, Coltrane was tempted away to the newly founded Impulse! imprint, the jazz division of the moneyed major label ABC-Paramount. Just two days earlier, he had recorded his debut album for his new label, Africa/Brass, but, before that could be released, he had to honour his contractual obligations to Atlantic and provide them with a farewell record.

When Coltrane arrived at Atlantic Records in March 1959, the jazz world was holding its breath, waiting with barely-contained excitement for the first fruit of a musical marriage that, on paper, seemed to promise much for both parties. The famous New York label, which had built its early success on rhythm’n’blues hits by Ruth Brown and Ray Charles, had been earning renown in the late 50s for its increasingly impressive jazz catalogue, which included groundbreaking recordings by Charles Mingus and The Modern Jazz Quartet. And the acquisition of Coltrane – who joined Atlantic the same year as the Texas alto saxophonist Ornette Coleman, who would set the free jazz movement in motion – was an exciting one for the label founded by Ahmet Ertegun and Herb Abramson in 1947. Coltrane already had one major album as a leader under his belt, 1958’s Blue Train, released on the iconic Blue Note label, and had gained much recognition for his catalytic role in the Miles Davis Quintet, which was expanding the frontiers of modern jazz. Given these two things, expectations were high for his Atlantic debut album, Giant Steps, which hit the record stores in January 1960 and was immediately received as one of the best Atlantic Records jazz albums yet.

A deep dive into modal jazz

Coltrane’s first album of all-original material, Giant Steps proved to be a shining beacon of instrumental virtuosity in jazz history: a jaw-dropping record whose totemic title track in particular redefined contemporary jazz with its combination of ravishing beauty and mind-boggling complexity.

The album was significant in Coltrane’s musical development because it marked the end of one chapter and the beginning of another for the saxophonist, who discovered that a more satisfying vehicle for his musical explorations lay in modal jazz, which was based on scales and used far fewer chords than bebop. A modal approach to jazz also facilitated looser, longer, open-ended structures and more freely flowing grooves, which Coltrane had experienced playing with Miles Davis on the title track of the trumpeter’s 1958 album, Milestones, and the whole of Davis’ Kind Of Blue album, released the following year.

Coltrane experimented with modal jazz for the first time on one of his own records, through the title track of his third Atlantic album, 1961’s My Favorite Things, on which he also switched to the unfashionable, higher-register soprano saxophone. Emboldened by the track’s reception and how it opened his creative floodgates, the saxophonist dove deeper into modal jazz with his next Atlantic offering, Olé Coltrane.

“When he is up there searching and experimenting, I learn a lot”

Released in November 1961, Olé Coltrane found Coltrane recording with his regular live group, a cutting-edge ensemble that featured the brilliant alto saxophonist and flautist Eric Dolphy, who was credited as “George Lane” on the first pressing of the album because he was contracted to Prestige Records at the time. The band’s rhythm section was formidable: pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Reggie Workman and drummer Elvin Jones would play an important role during the saxophonist’s Impulse! tenure. Reflecting Coltrane’s interest at that stage of his career in using larger ensembles, the group was augmented by the rising young trumpet star Freddie Hubbard – who could play hard bop and avant-garde music equally well – and a second bassist, Art Davis. The expanded group gave Coltrane a bigger and broader sonic canvas to work with, and the presence of Dolphy in the band – who was a leading light of avant-garde jazz scene – exerted a strong effect on the saxophonist, who told an interviewer: “When he is up there searching and experimenting, I learn a lot from him.”

As its title implies, the album’s side-long opening track, Olé, bears a Spanish influence and is thought by some to be based on El Vito, a well-known Spanish folk song. It’s also feasible that Coltrane may have taken Olé’s stylistic cue from Miles Davis’ modal-flavoured Flamenco Sketches, the closing track on Kind Of Blue.

Olé begins with strummed bass notes from Davis and Workman, who supply a solid but pliable foundation over which Tyner alternates between two chords a semi-tone apart. The piece is harmonically static, possessing a droning quality that characterised later Coltrane records. The rhythm section establishes a loose but free-flowing modal vamp over which Coltrane takes the first solo – blowing mellifluous filigrees of soprano sax – followed by Dolphy’s darting flute melodies, before Freddie Hubbard weights in with some adventurous horn lines. Tyner builds his solo on the foundation of the repetition of the opening two chords in a hypnotic see-saw-like effect that recalls his contribution to the earlier My Favorite Things.

“I like to play long”

Olé Coltrane’s second track, the Coltrane-penned Dahomey Dance, is another extended groove that begins with the two basses but which offers something different, this time reflecting the influence of African music. According to McCoy Tyner, Coltrane had been listening to a record made by musicians from Dahomey (now known as the Republic Of Benin) that employed two bass players. What results is a lightly swinging piece in which bluesy harmonised horns (with Dolphy, on alto, complementing Trane’s tenor) entwine over an ambling but infectious groove.

The album’s third and final track is Aisha, a gleaming exotic ballad written by McCoy Tyner which took its name from Tyner’s first wife, for whom it was written. The piece finds the saxophonist initially ditching the intense “sheets of sound” approach of the two previous tracks for an elegant simplicity in the way his tenor saxophone caresses Tyner’s achingly beautiful melody. Aisha was the second of only two Tyner compositions that Coltrane recorded during his career.

A multitude of ideas in a single improvised performance

By the time Olé Coltrane was released, the jazz world seemed more interested in where Coltrane was going rather than where he’d been; there was certainly more focus on the groundbreaking work he was doing at his new label, Impulse!, and, consequently, the album that marked his final Atlantic chapter has tended to be overlooked, even by some of the saxophonist’s staunchest fans.

But Olé Coltrane was an important release in Coltrane’s career because it demonstrated how his embrace of modal jazz set him free as an improviser, allowing him to explore a multitude of ideas in a single improvised performance that could be extended for as long as he had the creativity, the inclination and the energy to keep going. In fact, the 18-minute title track – the longest that Coltrane had committed to tape at the time it was recorded – was a perfect illustration of the saxophonist’s confession to Olé Coltrane’s sleevenotes author, Ralph J Gleason: “I like to play long.” In terms of its length, the piece was also reflective of how the saxophonist stretched out his performances on the bandstand, sometimes for as long as 30 or 45 minutes, as he explored a succession of musical ideas which came out as a continuous stream of melody.

Coltrane’s Atlantic adventure was relatively brief, but it yielded some important milestones. The magnificent Olé Coltrane stands among them: via its deeply searching quality and use of elongated structures, the album pointed the way for Coltrane to continue to elevate himself among the best jazz saxophonists in the world with future endeavours such as his spiritually inclined magnum opus, 1965’s A Love Supreme.

Find out where ‘Ole Coltrane’ ranks among the best Atlantic Records jazz albums.

More Like This

How Yes’ Self-Titled Debut Album Planted The Seeds Of Prog-Rock

With a sprinkling of psychedelia, jazz and classical influences, Yes’s debut LP offered bounteous hints of a prog-rock harvest yet to come.

‘Stand Up’: How Jethro Tull’s Second Album Broke The Blues-Rock Mold

Leaping beyond their bluesy beginnings, ‘Stand Up’ saw Jethro Tull pioneer a baroque fusion of ‘cocktail jazz’, English folk and hard rock.

Be the first to know

Stay up-to-date with the latest music news, new releases, special offers and other discounts!